Astrid Preston

ON REFLECTIONS

Exhibition at Craig Krull Gallery

March 7– April 11, 2015

INTRODUCTION

by Craig Krull

Astrid Preston’s work is testament to the fact that landscapes do not exist in Nature but rather, only in the mind’s eye. While her images employ elements of place, they are also reconstructions that manifest personal perspectives or conceptual themes. In this way, she is a kindred spirit to Edward Hicks and his Peaceable Kingdoms, Giorgio de Chirico and his vacant metaphysical piazzas, and René Magritte and his surreal scenarios. On Reflections, the title of Preston’s new group of paintings, refers to her subject matter, but it also suggests her cerebral processing and interpretation of nature. The ponds at Descanso Gardens in Southern California and Monet’s garden at Giverny, France serve as inspiration to her meditations. In fact, these gardens and the idea of gardens in general, are aesthetic re-creations, idyllic ideals, the Plato’s Cave of Nature. Our expulsion from the Garden of Eden is symbolic of our disconnect with a Nature that we are perpetually attempting to re-establish. Within the artifice of a garden, Preston has chosen to focus on reflections, not the trees and plants themselves, but shimmering mirror images of them. As in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There, Astrid Preston’s paintings explore the other side of the mirror, the reality that we construct in our minds. In this body of work, her handling of paint continues to evolve, absorbing elements of Milton Avery’s washy daubs and Charles Burchfield’s wiggly wormy lines. She has also introduced seemingly anomalous molecular-web balls that drift throughout her landscapes, suggesting the eye floaters in one’s field of vision, or even our scientific attempts to understand the basic structure of all things.

ESSEY

The Attentive Eye: Perception and Vision in the Art of Astrid Preston

by Robert L. Pincus

On Reflection, 2014, oil on canvas, 57 x 78 inches

It has become a commonplace of contemporary thought to point out that our bonds with the natural world have grown increasingly more tenuous, ever more filtered through a cultural veil. Andy Warhol was prescient on this development, compressing this notion into his droll series, Flowers, 1964–1965, in which the imagery of Hibiscus is drained of any life—lifted, as it is, from a spread of magazine photographs by Patricia Caulfield, silkscreened onto canvas and overlaid with bright and unnatural colors. His conceit is of nature filtered through photography and film, becoming banal in the process. But this logic left out—and leaves out—something important: even those who generally experience nature from afar, filtered through our post-industrial landscape, are never truly divorced from water, sky or earth, except perhaps mentally. Body still balances mind in this equation.

The late Donald Barthelme, in his characteristically brilliant and surreal way, summed up this cultural scenario in a story from his collection City Life, 1970, entitled “Brain Damage.” The subject: “blue flowers.” His narrator conveys a debate about what to do with them: should people let them be or wire them up? “The humanist position is not to plug in the flowers,” the narrator explains, “to let them alone. The new electric awareness, however, requires that the flowers be plugged in, right away.”The debate, as he frames it, is seemingly absurd—true to the comically logical illogic of the Barthelmeesque universe. Wiring up flowers? Yet it contains a sideways truth about our relationship to nature and how we alter it. Barthelme’s narrator in “Brain Damage” just can’t bring himself to side with the school of “electric awareness.” His view is “somewhere between these ideas, in that grey area where nothing is done really, but you vacillate for awhile, thinking about it.1 He simply ends up simply appreciating the blue set against the grey, as he puts it.

This really isn’t vacillation at all. It’s a middle ground. He can’t reduce nature to the mass media version of itself, as Warhol did. You might say that the irrepressibility of color that Barthelme describes—blue erupting in a grey terrain—is one and the same impulse that makes landscape painting of enduring relevance. We have a need to keep clarifying and vivifying our bond with water, sky and earth.

Which brings me to one of the most involving landscape paintings I have encountered in my three decades of writing about art: Astrid Preston’s Mountain Path, 1989. It makes this bond feel insistently relevant. She has described the impetus for this image as one rooted in a straightforward question she posed at the time—a simple question touching on both artistic vision and direction in her life: “Where am I going?”2 But like many statements of intention, it doesn’t reveal how the artist travelled from point A to point B, how she shaped that question into a beautifully realized painting. Mountain Path isn’t so much an image of a place as a vision of an ideal place. In a sense, the painting is allegory made visible. The image is the answer to her question. In creating a painting about a path she created a symbolic path that distilled what she has been doing in earlier work and pointed the way to future paintings.

There is a readily discernible order in its gently curving path, which divides the scene from top to bottom. It is a place teeming with the life of trees—just look at the variety of them—and yet utterly still. It invites you in, but at the same time you feel as if any figure would be an intrusion. It carries implications of paradise, though it needs no symbolic Adam or Eve. The image is also just naturalistic enough to suspend disbelief, but unreal enough to appear like a dream of nature. It is nature as we might wish it to be: the magnetism of the image is a tribute to Preston’s keen understanding of pictorial space and unerring use of color and form here.

Mountain Path was part of an evolution in which architecture had become increasingly less of a presence in her images; for the most part, it has disappeared. This shift is intriguing. Houses, which appear first as cut aluminum and painted forms (1980–1983) and then as elements in canvases (1983–1987), create an aura of suburban stillness, with an emphasis on their geometric contours in the chosen houses. They look as unpopulated as the landscapes would later, but are less at a remove from everyday life.

Nonetheless, mirroring her contemporary Los Angeles landscape, urban or suburban, was never a dominant theme in Preston’s paintings and has essentially disappeared over time. The architecture in her work has always been iconic and decisively symbolic. Houses look as if they are vessels or containers for light, an effect carried to dramatic effect in Light Wall, 1986 and Ellwood House, 1987. Circle of Light, 1986 embodies both day and night within its image: the house on the left is shrouded in dusk and the grounds on the right are radiant with sunlight. At the same time leaving houses behind isn’t a denial of human presence in her pictorial universe. In Mountain Path, the path itself is a thing of artifice, of course.

Yet the evolution of Preston’s vision and its refinement has never been linear. It rarely is for any artist with a sustaining vision such as hers. The subjects shift, the focus changes; yet there is the sense of essential themes and motifs that unite different series and different decades in her art.

The passion for order and structure in much of the work from the 1980s remained within the strictures of a unified picture, even when she didn’t adhere to the traditional notion of mirroring nature. For example, compressing night and day into the same scene in Circle of Light subtly fractured the mirror, as it were. By the early 1990s, though, Preston had found a fresh way to split the difference between representation, as she had practiced it, and abstraction from nature, as it fit within the ways she wished to expand her vision. Her body of work—if we look at the drawings and paintings she produced throughout the 1990s or consider her oeuvre as a whole—reminds us that mirroring nature requires just as much artifice as freely altering it. Of course representational art often seeks to conceal overt signs of structure; otherwise, the illusion of the real is interrupted and the pictorial spell is broken. This is a Western ideal, going back to the Greeks of course and reaching forward until the rise of Modernism in the late 19th century. It is also a highly sophisticated ideal. As the great Victorian era art critic John Ruskin famously remarked, “ The truth of nature is not to be discerned by the uneducated senses.”3

Ruskin knew that this “truth,” as it related to art, was not tied to one approach to painting or any of the other visual arts. Versions of it are of necessity tied to learned ways of both creating and viewing art. It’s not too much to say that Preston’s paintings are steeped in the kind of educated vision to which Ruskin alludes, even as they are informed by developments in art about which he simply couldn’t have known. There is a good deal of modernist history—and the modernist tendency toward scrutiny of art making itself—embedded in paintings such as Green Red Yellow, 1991, Provence Garden, 1995 and Green Heart, 1999. All divide the picture plane into multiple images. Green Red Yellow contains three seductively detailed landscapes, thick with trees and each similar but distinct from the others; they are also distinguished by a different emphasis in palette suggested by the title. Provence Garden and Green Heart each contain pictures within a picture: small rectangular scenes within the large scene: the first with its meticulously manicured version of verdant nature; the second with the way it depicts a section of forest, cropped photographically, and surrounded by a larger wooded scene.

What is both striking and pleasing about all of these paintings is the counterpoint between the mirror of nature and just how Preston deftly interrupts it. Or, to say this differently, the way she employs “the mirror” in such a way that draws attention to the mirroring effect as well as other forms of pictorial invention. Unless the viewer is a slavish admirer of traditional realism, the interplay in her pictures of one scene with another within a single panel is sure to be a source of delight. It is a parallel to the variety of pleasure that we derive from a play within a play, as in Hamlet; or to the way that Tom Stoppard’s play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead , 1966 refers us back to Hamlet by amplifying the story of two minor characters from the play. Just as one story enriches another in these examples, one picture expands the effect of others in each of these paintings.

Preston takes the idea of image within image into more complex territory with paintings like Floating Worlds, 1996. It is a fantastical composition: miniature circular views of landscapes levitate within a misty view of smooth field and expansive trees. The atmospheric softness of the larger scene is a perfect visual foil for the sharply focused scenes within each of the small floating circles, which each function as a miniature slice of the world. Two other things that make these circles so effective: the first is the tension between the diminutive size of the image and the implied largeness of the landscape it pictures; the second is the implication that the large scene is a gateway to a group of worlds. This is surrealism of a highly subtle kind.

Fusing such disparate foci into one composition, as in Floating Worlds and related paintings, clearly presented new vistas for Preston. She used that opening to great effect, multiplying her foci in other ways. She employed magnification rather than miniaturization in the lush Pomegranates, 1997; in it fruit are large and the landscape, which in realist terms would be larger, is now smaller and centered within the canvas. The picture in the middle of this painting scene is akin to a window on a disparate place. It is an artistic order imposed upon the landscape, arbitrary in some measure, but made cogent by the painter’s imagination.

In paintings soon to follow, she turned away, for a time, from pictures within pictures and toward a plenitude of flora within a single scene. The shift is first evident in desert scenes, all from 2000, which present beauty through repetition: High Desert, Green Desert and Desert Path are luminous examples. They do for arid and terrain what Vija Celmins did for the sea: take what appears random and give it a rhythm of form and variation. Desert Path can be seen as a companion picture to Mountain Path, in that each possesses a path that gently divides the scene and a trail suggests the human presence within an otherwise natural scene. The rounded shapes of the low-lying vegetation in Desert Path stretches to the horizon, positioned high in the canvas. Your eye follows the progression of plants just as it follows the curve of the path. One of the other pleasures of this picture is the seductiveness of its palette: soft blues, greens, purples and related hues. The colors accentuate difference just as the serial nature of the vegetation emphasizes repetition.

The pictorial insights from these painting segue smoothly into the forest scenes. The sense of structure that is so persuasive in Desert Path and the related paintings, with its variations on form and its graceful shifts in color, is similar in the likes of New Growth, 2001 and Bare Trees, 2002. In the first of these examples, it is the triangular shape of many pines, in different tones of green that established an almost oceanic pattern; in the second, it is the skeletal look of the trees that creates the repetition and variation. In both these and other forest scenes, the woods encompass the entire canvas; there is no horizon line. The effect is to make pattern the focus. And together, all of the paintings from this period—desert and forest pictures—trigger a question: is the order there in nature itself, waiting to be highlighted, or is she creating it? The answer has to be both. The order may be embedded in the scene as found, waiting there as potential. But the eye and mind of the discerning artist discovers it.

Still, order can create a desire for the opposite, or the semi-opposite might be more accurate: less order and less structure. This is evident in Surrender, 2005, in which Preston’s composition does in fact surrender to the sheer abundance of detail and complexity of nature: more specifically, a hedge with leaves so numerous that its detailed realism verges on abstraction. Repetition and variation create no discernible pattern and yet the overall effect is seductive. Preston worked a good deal from photographs in this work, in which leaves became the prime form, and likens the approach to photo-realism. But she also emphasizes “how abstract [was] the pattern that the sun created on the leaves.”4

This comment reiterates a quality fundamental to Preston’s art: a keen sense of the relationship between representation and abstraction as well as the way that relationship can assume myriad forms. A source for her approach to that relationship, reaching back to the early 1990s, was Japanese and Chinese painting. But that passion gained increased prominence in her work about 2009; at that time she started spending more time in Japan, beginning when her son moved there during his last year of college and made it his home. East West, 2009 suggests this shift in its title, in the botanical forms it pictures and in the way the leaves and flowers, meticulously rendered, exist in abstract pictorial space.

In her continuing exploration of this sense of space Preston has adapted a key principle of Chinese painting. The great art historian E.H. Gombrich describes this broad concept in his enduring book Art and Illusion. Commenting on a maxim of Chinese art theory of the 17th century—i tao pi pu tao (idea present, brush may be spared performance)—Gombrich observes, “Perhaps it is precisely the restricted visual language of Chinese art, with its kinship to calligraphy, that encouraged these appeals to the beholder to complete and project. The empty surface of shining silk is as much a part of the image as are the strokes of the brush.”5 Substitute linen for silk and we would have one way of seeing how Preston altered her approach in a painting like Branches on a Blue Sky, 2010, in which leafless branches set against an expanse of sky extend into the unpainted area of linen that surrounds this territory in blue. The effect creates the suggestion of a broader vista than what it pictures; what is not painted contributes to the character of the composition as much as what is rendered. She employs the dimension of the empty surface to equally rich effect in several paintings including Magnolia Blossoms, 2010 and Red Pines on the Slope of Higashiyama, 2011. Preston achieves a comparable economic elegance in an essentially monochrome composition in which the gnarled branches of a stately tree extend across four wood panels in Black Pine Ginkaku-ji, 2012. The attention to detail in these paintings marks a new emphasis on individual forms in nature: the single blossom, the lone leaf, and the isolated branch. Preston had always employed detail to strong effect: consider the attention to each leaf in paintings like Surrender. But it takes on a greater weight in paintings like Branches on a Blue Sky and Sycamore Branches, 2013.

Given her sustained attention to landscape painting in its many dimensions, it doesn’t seem surprising that the lure of the garden as subject has grown stronger for Preston. The beautifully maintained grounds surrounding the houses in her paintings of the 1980s are the suburban echoes of Roman, French or English domestic landscapes. A painting such as Provence Garden makes this interest explicit. The garden as landscape is a great and venerable subject for painters. As cultural historian Leo Marx succinctly writes, “The ancient image of an enchanted garden gave the first serious painters of landscape their most workable organizing motif.”6 His observation has clear relevance for Preston’s current work. The focus on gardens also dovetails with the increased time spent in Japan, during the past six to seven years and a keen interest in traditions in Japanese and Chinese art that reaches back two decades. The series focusing on Descanso Gardens in Los Angeles County is a significant marker of this interest. Given that it contains a Japanese style garden and pavilion among its exhibits, the site itself is emblematic of the Western passion for Japanese culture, a collective interest that is a manifestation of Modern European and American cultures reaching back to late 19th century France and the rise of Japonisme. Preston’s paintings from this series manifest a style of beauty that marks a shift in style for her. Much of the distinctiveness of Preston’s imagery has been rooted in a precise presentation of imagery, linear in its emphasis. Descanso Lake Reflections, 2013 diverges. Rendering the landscape in the water virtually necessitates that the play of form and color is softer, more fluid—in essence, more painterly than in earlier work. This change is really an expansion of Preston’s consistent fascination with the structures that nature reveals to her as a painter.

|

|

| Chinese Pond, 2014, oil on wood panel, 38 x 52 inches | Reflection at Tea House, 2013, oil on wood panel, 38 x 52 inches |

It is important to acknowledge that painting on wood has been instrumental in her loosening of forms and softening of her palette. Surface and results are inseparable. Sweet Spring, 2013 shows us as much, the grain of the wood becoming a source of pattern in the rendering of shore and water. The attention to water, here and in general, has had a strong effect on her work, perhaps inevitably, since perception always goes hand in glove with aesthetic design in Preston’s art. Seeing landscape through the mirror of water has loosened the structure of her paintings.

The world of gardens, highly aestheticized landscapes in their own right, have yielded numerous subjects. In addition to the Descanso Gardens, the Japanese Garden at the Huntington Library, Art Collection and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California and Claude Monet’s garden at Giverny have been significant sources. These paintings express a deep appreciation and passion for the “artificial” landscapes of Japanese style gardens as well as Monet’s garden, which was deeply informed by Japanese precedents. But they are distinguished by the way she looks for new ways of seeing them and recasting them in her paintings. They also manage to pay tribute to Monet’s Impressionism without recycling its stylistic tropes.

Mirroring, 2014, oil on canvas, 57 x 78 inches

Mirroring, 2014 is a touchstone of the current state of Preston’s art, just as surely as Mountain Path and Floating Worlds marked earlier points in her oevre. It possesses complexity without any chaos and calibrates the relationship between a place and its reflection gracefully. It exerts a visual pull in the way clear water segues gently into reflections of flora and then tugs your vision to the water’s edge and beyond, where a multicolored sheet of vegetation slows the travels of your eye. There is a pregnant tranquility to this scene, a mood analogous to that of Return to the Pond, 2014, (p.20) which has a smaller expanse of water and a handsome flourish of green vegetation rising from the surface of the pond. One dimension of the complexity in this group of ambitious paintings is the shift between sharp and soft focus. Night Curtain, 2014 (p.18) is a prime example, in which crystalline clarity in the foliage in the foreground is a counterpart to the atmospheric horizontal tendrils of color that interrupt a predominantly black background—a bright flourish in a dark plane that fulfills the title of the painting.

|

|

| Return to the Pond, 2014, oil on canvas, 57 x 78 inches | Night Curtain, 2013, oil on canvas, 57 x 78 inches |

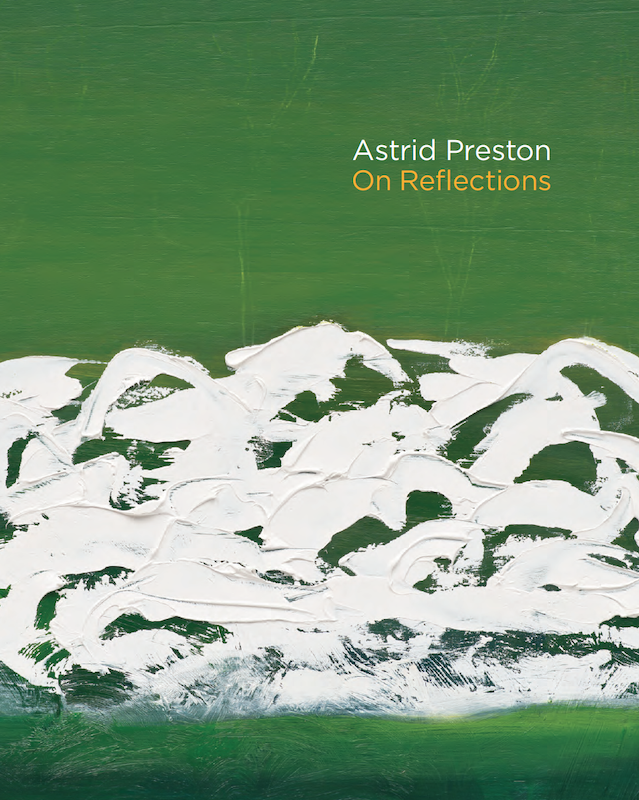

As much as expansive landscapes are central to the current work, another constant in Preston’s art is her resistance to a singular style. She remains devoted to a multiplicity of vision. Patterns of orbs punctuate select pictures, a geometric motif that is organic in spirit and abstracting in effect. In Red Reflections, 2014, (p.32) the orbs appear to float within water and are finely focused; in Riverrun, 2014, (p.33) they are ghostly, seemingly fading away. In Some Memories, 2014 (p.39) there are two kinds of spheres: monochrome versions similar to those in Red Reflections or Riverrun and tightly focused circular landscape fragments like those in Floating Worlds. But Preston also takes delight in casting aside the polish and sophistication of her paintings to try for what she calls primitive effects. The results in White Waves, 2014 (p.25) are lush, seductive, and, in a departure from her intent, quite elegant. The tangle of thick white brushstrokes evokes white foam in an expanse of green.

|

|

| Red Reflections, 2014, oil on wood panel, 16 x 16 inches | Riverrun, 2014, oil on wood panel, 16 x 16 inches |

|

|

| Some Memories, 2014, oil on wood panel, 24 x 24 inches | White Waves, 2013, oil on wood panel, 16 x 16 inches |

The different ways of working are ultimately part of a larger picture, a bigger odyssey. Preston’s art, seen in its full sweep, becomes the pursuit of a kind of knowledge that can only be gained through creating a sustained body of work about natural terrain and natural life. It is knowledge that is intimately tied to the observation of natural forms. Ralph Waldo Emerson described the process well in his great early essay, Nature (1836), when he declared, “To the attentive eye, each moment of the year has its own beauty, and in the same field, it beholds, every hour, a picture which was never seen before, and which shall never be seen again.” Preston has remained sharply attuned to such flux, shaping her perceptions into something larger: a vision of landscape that heightens our sense of its beauty in all its complexity. She also affirms the way that the bond with earth, water and sky, while primal, is also inseparable from the intangibilities of the imagination and the human spirit. Invoking the terms of Barthelme’s story, the stance of electric awareness just won’t do; like his narrator, Preston isn’t about to relinquish the humanist perspective, even in a world that sometimes makes us think the colors of nature could fade from view.

|

|

| Summer's Light, 2014, oil on canvas, 57 x 78 inches | Everywhere, 2014, oil on wood panel, 38 x 52 inches |

Notes

- Barthelme, Donald. “Brain Damage,” City Life. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970. 134. Print.

- Preston, Astrid. “Overview of Paintings.“ Message to the author. 10 November 2015. E-mail.

- Ruskin, John. The Genius of John Ruskin: Selections from his Writings. Ed. John D. Rosenberg. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1964. 23. Print.

- Preston, Astrid. “Overview of Paintings.”

- Gombrich, E.H. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1960. Princeton/Bollingen ed. 1969. 208-210. Print.

- Marx, Leo. The Machine in the Garden. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1964. Reprint ed. 1977. 38. Print.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Nature.” Ralph Waldo Emerson: Essays & Poems. New York: Library of America. College ed. 1996. 15. Print.