Astrid Preston

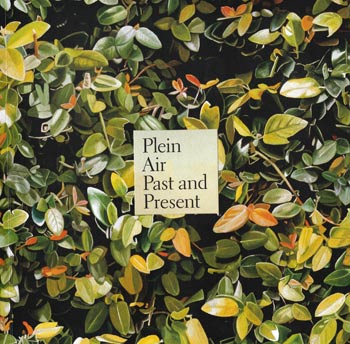

PLEIN AIR: PAST AND PRESENT

PLEIN AIR: PAST AND PRESENT

by Reesy Shaw, Director, Lux Institute

LANDSCAPE – A SUBJECT MATTER that had been traditionally “background” became “foreground” for artists working in the mid to late 19th century. In confronting the outdoors directly, these painters packed their supplies and drawing materials to work outside. Undaunted by terrain and weather, artists a century ago stood in the open air to sketch or paint the land around them.

Here they were able to see the natural world up close, to better portray sunlight and shadow on field and foliage. Some of the first practitioners of what we now call “Plein air,” the French Impressionists and their followers, charged these rural scenes with a striking energy and light. They painted glowing and often wind-swept meadows with gestural brushstrokes that suggested verdant plains, mountains and haystacks. Much of the impact of this work, first practiced by Monet and the unrivaled Van Gogh, was imbued with the physical energies and the “impressions” of these painters. In the late 1900s, plein air painting made its way to the United States.

In tandem with the rush outside by many artists on both sides of the Atlantic came the evolution of a new artistic medium; the discovery of the Daguerreotype and Calotype allowed for a more “literal” focus. With these photographic tools new vistas were captured, cityscapes as well as rural landscapes. These subjects were selected because they remained still during the long exposures necessary to affect the primitive film.

Painters such as Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) used photographs to help frame and record their subjects. Even Degas used the camera to capture the gestures of the people he painted. In these early days of photography, the use of the camera as an artistic tool was frowned upon, so when the early Impressionists used a camera they destroyed the evidence afterward. Historians were surprised to find two hundred and fifty negatives in Degas’ studio after his death.

In the past century it is the ubiquitous camera lens that has transformed the artist’s vision and consequently our own view of our surroundings. The impasto landscapes of San Diego’s Maurice Braun, Alfred Richard Mitchell and Charles Fries, like other plein air painters, have the soft focus and coarse outlines of local rural scenes. They speak to an earlier iconography that developed as artists stood in front of their easels and “roughed out” what they saw. The desert landscapes and sea scenes have pastoral warmth and forms that suggest “a broad brush” in contrast to the explicitly detailed foliage that a focused lens affords. It is this detail, this fixed and objective imagery, which has transformed contemporary landscape painting and, as a result, the way we now see the world.

Stockholm-born and Los Angeles-raised and educated, Astrid Preston was first attracted to nature as a child in Sweden, where she grew up in a house next to an apple orchard. Her babysitter remembers her as a three-year old, painting apples from neighborhood trees. As an artist, Preston’s pursuit of landscape painting has been singular and relentless. Starting with her earliest canvases in the 1970’s, she has examined nature in exquisite detail; moved by distant memories, outdoor observations, and perhaps most profoundly, by the camera’s lens.

Preston finds magic in nature, using the camera as her “notebook.” Traveling in Japan, she photographed light as it filtered through leaves and branches and took pictures of birds instead of buying a bird book. She is charmed by her photographic investigations and feels she is “appropriating nature.” She finds dead leaves beautiful and relates to them as metaphors for loss. Everything in nature for this artist alludes to the life cycle- so she works from “nature,” not “culture.”

In the act of painting, she’s looking for a little “wildness” – something other than the cultivated and the natural. Her recent technique is to “give up the sky.” By removing the horizon line and painting plants on the ground, she has found a subject that goes on forever.

In a small square format, with a very tiny brush, over hours, weeks and months, she paints her leaves and vines as an endless carpet. While these views may be as simple as a fragment of ground cover on the slope outside her kitchen window, the tone and shape of this segment of nature speaks to the world we all inhabit. There is war in these paintings – for Preston bare branches are soldiers and bushes a cemetery. These simple elements tell stories, create moods and speak of the artist’s inner life as she reveals our outer world in a way we have not seen before.

Excerpt from PLEIN AIR PAST and PRESENT

by D Scott Atkinson

Chief Curator & Curator of American Art, San Diego Museum of Art

Among the many artists who continue today to seek direct contact with nature through the plein air practices established by Durand is the Swedish-born artist, Astrid Preston. Her painting Surrender marks the “present” in the Museum’s presentation of Plein Air Past and Present. Primary to Preston’s working method is the enlargement of nature’s most intricate details – to massive scale. Her meticulous rendering of foliage fills the eight foot canvas from edge to edge, unleashing powerful forces in the juxtaposition of colors, textures, shadows and reflective highlights while placing emphasis on the facts. In this regard, Surrender strongly parallels the intense scrutiny Durand applied to his own nature studies albeit, on a much smaller scale.

Plein Air Past and Present gives testimony to the enduring legacy of Durand’s call, “Go first to Nature.” Whether searching for bucolic poetry or the transfiguring effects of brilliant light, these artists sought a kinship with nature by channeling its innate beauty and inner spirit onto canvas.