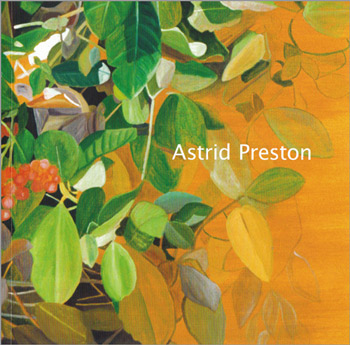

Astrid Preston

ASTRID PRESTON: NEW PAINTINGS AND DRAWINGS

Laguna Art Museum

October 15 – December 27, 1987

by Peter Clotheir

Form is emptiness

Emptiness is form

Emptiness is not other than form

Form is not other than emptiness

--The Heart

Sutra

To spend time with Astrid Preston’s paintings is to be aware of the constant presence of an observer—at once analytical and playful, restless and serene, an eye that insists on keeping its own contemplative distance even as it beckons us courteously to join in on its meticulous expeditions into the natural world. Surrounded one recent day in Preston’s studio by the paintings that have occupied her attention for the past three years and more, I could not help but be struck by the way the lens of that observing eye has tended to “zoom in” on its object as her work continues to grow. It has now closed in so intimately that it requires us to accompany the artist through and beyond the obvious attractions of the surfaces she paints with such consummate patience and skill: having led us through the landscape of her mind’s eye for twenty years and more, Preston now invites us to penetrate between the stems and foliage and gaze into what lies beyond.

Always clear-sighted, precise—at times almost severe—Preston’s work combines the appeal of external serenity with undertones of an inner disquiet that subverts our impulse to settle for the comfortable visual gratification of traditional landscape. Those familiar with her earliest paintings from the 1970s will recall their concern with the underlying structure of the world she was investigating. Her deconstructions of the archetypal image of suburban houses took the form of irregular assemblages of enamel-painted architectural fragments on cut-out aluminum. They were influenced no doubt by Preston’s personal history, for her parents were both architects, immigrants to Southern California from post-World War II Europe, and it may well be that the young Astrid inherited from them, along with an instinctive grasp of the inner architecture of her subjects, something of the exile’s nagging sense of loss, of deracination and alienation—a sense of otherness.

Certainly that feeling pervaded Preston’s paintings when she first began seriously to address the matter that remains her interest today: the natural environment. Near Paradise, 1986, for example, typically conveys a powerful sense of longing, of standing outside, always “near” but never quite “there.” The corner of a rationally-designed maze and the vertical bars of the cypress trees stand between us, as viewers, and the Eden beyond—a pacific landscape of comfortable green pastures, rolling hills and lanes and a tiny, tranquil homestead, tucked almost out of sight. Our eye is invited to contemplate this “paradise,” but is discouraged from trespassing too far into its seductions. The image evokes not only a separation between self and other—that old, perplexing dualism—but also between heart and mind. Or perhaps, more accurately, it suggests the power of the rational, analytical mind to block access to the heart.

Formally, too, this painting allows a glimpse into the artist’s on-going inner debate between the modes of representation and abstraction: here the formal, “abstract” patterning of the maze and cypress trees stands in marked contrast to the “natural” flow of the landscape beyond. By this time, Preston had staked her vision as a contemporary artist on representation in a time that had become high-risk for the art of painting itself—declared dead, as you’ll recall, by a powerful cabal of critical theorists emerging from the heyday of conceptualism. A special circle of aesthetic purgatory had been reserved for painters who dared to indulge in dialog with the world of external reality; and “beauty”—remember?—was way beyond the pale. Preston, however, with inarguably beautiful paintings like Near Paradise, was already ahead of the game, embarked on that search for what concerns many post-painting painters to this day: a workable ground between the centuries-long tradition of representation and the twentieth century innovation of abstraction.

In fact, that had always been Preston’s path—as I suppose, when you get right down to it, it is every painter’s path. It lies in that imaginative area between what the eye seems to see and what the mind invents, the “real thing” in the world out there and the other, very different reality of paint on canvas. Progressing further along this path in the 1990s, Preston arrived at a different strategy, working with rectangular inserts in her landscapes—small paintings within paintings—to surprise and confound the eye and to counter the “realist” expectation with purely imaginative, aesthetic demands. Thus in Lemon Tree, 1995, four small landscapes are pictured hanging from the branches of the tree, begging comparison with the exquisitely-painted fruit themselves, and asking viewers to radically reframe their points of reference. Here Preston brings a gentle irony into play to demand reflection, as did Rene Magritte in a comparable strategy, on the paradoxical relationship between art and nature, even as she requires attentive viewers to re-assess the “reality” of both.

This strategy of insertion revealed more of its special meaning in Green Heart, 1999, a painting made at the time of a heart attack that threatened the life of Preston’s father. Here, the strategy changes: the image in the central panel is now continuous with the image of the foliage that surrounds it. Only the palette changes, from the “green heart” of the central rectangle to the grisaille of the surrounding forest, suggesting the persistence of life amidst the ever-present human condition of mortality. Here, too, Preston’s personal emotional investment in the landscape becomes unambiguously explicit in the powerful, yet subtle contrast she establishes between the vitality of colorful foliage set against impenetrable darkness at the center of the painting, and its burned-out, ashen absence at the edges.

The horizon line placed close to the top edge of Green Heart reminds us that Preston’s view-finder, around this time, is tending more and more to exclude that anchor to the perspectival approach that has traditionally dominated Western landscape painting, and which has by now become extraneous to her purpose. (She speaks of her debt, in this context, to Chinese landscape painting, “freeing the landscape from the horizon line.”) She plunges us instead, head-first, into an extravagant, edge-to-edge field of vegetation, where we sacrifice the rational comforts of orientation—knowing where in the world we are—to the experience of sheer, glorious, overwhelming, decontextualized presence. The experience is akin, as I imagine it, to what Buddhist teaching calls “groundlessness,” where the context that gives the illusion of stability and meaning to experience disappears and we are left with nowhere to stand but in the present moment.

While subsequent works like Spring Forest, 2001 and Maple Red, 2002, do not abandon Preston’s abiding insistence on strong structural underpinning, they sublimate it in the subtle patterning of tree trunks, branches and foliage, and in the artful arrangement of passages of color. We are aware of being in the presence of nature—but nature processed through the vision of the artist into a picture plane that transcends the objective appearance of its component parts and coalesces into a rich complex of human sense perception, intellect and feeling. In other words into experience itself.

Preston’s paintings of the past two years have pursued the avenue these earlier paintings opened up, but they have zoomed in still closer on the natural subject matter. Instead of trees and forests, we now encounter greatly enlarged, over-all visual fields of leaves and blossoms whose framing, though surely a reflection of the artist’s selective eye, seems almost arbitrary. More and more, Preston says, she finds the representational quality of the image to be superfluous to her painterly objective. “My recent paintings of plants,” she has written, “come from observing how sunlight reflecting off leaves creates abstract patterns. I find that the more attention I pay to the reality of the image, the more abstract the image becomes.”

Absence, 2007, made at another moment of personal anguish, at the time of Preston’s mother’s death, provides an excellent example of the phenomenon she describes. The large central “diamond” effect suggested by the diagonal thrust of supportive stems creates a strong, quasi-geometric structure within the larger square of the 32” x 32” painting. Meticulously observed and painted in this structural context, the natural-world reality of the leaves and blossoms evanesces through the artist’s hand—and under the viewer’s gaze—into the alternate, “abstract” reality of the painting: given an attentive eye, we can catch this act of prestidigitation in the act of its happening: stand back, and we enjoy the illusion of observing nature. Come close, and all we see is a rendering in paint of the effects of light and shade. Preston has brought us in so close in these new paintings that the first option recedes even as our eye is occupied with the second.

Abstraction, though, also betokens something deeper than its common aesthetic association, and Absence, in its very title, brings this other significance to our attention. At one level, surely, it is emotional: a sense of loss, the grief we experience at the sudden absence of a loved one from the world we have shared with them. That absence is suggested in the painting by the way in which the foliage parts, at the center, to lead us into a dark inner core, where definition disappears and the unknown, unknowable, indescribable awaits, refusing to reveal itself to the eye or mind, a sink hole that acts as a vortex for the eye, inviting it on a journey, as I suggested at the outset, into what lies beyond the seductive surface.

What, then, is this “beyond”? In part, it is what lies literally behind the foliage – the decaying undergrowth and the adjacent area of unoccupied space, rendered as pure abstraction – that is given more and more of the picture plane in works like Near the Edge of Light, 2007, (p.23) and Moment into Moment (p.31-32) a large four-part painting also from last year. At a deeper level, however, it is the joyful experience of that groundlessness I mentioned earlier, the loss of all explanatory context, whether temporal or physical, and an absorption into the experience of pure, unattached presence. It is the point at which Preston’s newest work – in paintings like Pink Hawthorne, (p.29-30) for example, or the gorgeous In the Company of Spring, both from 2007 – serves to pluck us out of our small selves with all their expectations, all their attendant ego needs and attachments, and leave us finally unmoored, adrift in the immediacy of the moment and the act of contemplation. It’s the point at which, for me, the perennial mystery of The Heart Sutra begins to offer up just a brief glimmer of its ineffable meaning: Form is emptiness, Emptiness is form… Before it evanesces once again as the mind attempts to grasp it, with its imperious need to understand.