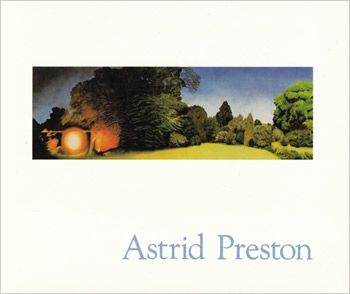

Astrid Preston

NEAR PARADISE

Laguna Art Museum

October 15 – December 27, 1987

By Robert L. Pincus

Introduction

In forging a vision of the Southern California landscape, Astrid Preston began with fragments: paintings on aluminum cut to the shape of a house; spare arrangements of a scene arranged to suggest an entire panorama; arbitrary wall mounted shapes which encouraged the viewer to piece them together into a larger picture. It is the forms of this landscape that are the explicit subject of these works from the shape of a California bungalow to that of the ubiquitous palm tree They are clearly focused on form, though not entirely formalist. They possess symbolic resonance too, since a good number of them are the conventional icons of Southern California as 20th century paradise.

In retrospect, we can see a central theme of Preston’s work is adumbrated in these paintings of 1980 to 1982. But it was only after she began integrating her formal vocabulary into larger scenes, after she began painting on rectangular panels, that she confronted this mythic image of Southern California as a latter day Eden.

I use the term “confronted” because there is a deep-seated ambivalence in her work toward the face of this landscape she has chosen as her overarching subject. There is something simultaneously lovely and foreboding bout the scenes she represents. The land is verdant, the houses are graceful and the vegetation is rich, but the depicted locales all look vaguely foreboding. If I imagine myself to be entering any of here scenes, it is only with caution. In short, what could be a paradise ultimately is not.

Preston’s paintings are not self-consciously symbolic, for her composing process is closely connected to observation. Ideas for her larger paintings have evolved out of her Notations, small colored pencil studies arranged in grid fashion – several to a sheet of paper. More recently, she has painted tiny canvases in much the same fashion - as a working “journal” of ideas. Photographs, too, arranged in composite fashion, are important sources for her canvases.

But her most ambitious pictures, such as those represented in this exhibition, depend as much on her mind’s eye as her eye. Preston fuses disparate scenes – and part of the eeriness of her paintings derives from this technique. A portion of a scene can appear to be bathed in daylight, while another is shrouded in twilight. Consider Forest Gate (1987), where the sun is setting over the house and trees but the lawn off to the left seems to be radiant with the light of an earlier hour. Circle of Light (1986) fuses two distinct scenes into one: the house is shrouded in dusk while the grounds to the right are brightly lit by the sun.

What this argument suggests is that Preston is a landscape painter who is also a subtle but potent social critic. As social critics go, she is a gentle one. It would be hard to imagine, say, Eric Fischl’s self-absorbed types cavorting on her lawns or carrying on inside her houses. Yet like Fischl, she touches on the mood of rootlessness, dislocation and radical alienation which is so central to contemporary American life. Nor is she as disheartened by the ahistoricity of the Los Angeles landscape as novelist Nathaniel West, who was to comment in Day of the Locust (1939): “Only dynamite would be of any use against the Mexican ranch houses, Samoan huts, Mediterranean villas, Egyptian and Japanese temples, Swiss chalets, Tudor cottages and every possible combination of these styles that lines the slopes of the canyon.” Yet Preston quietly chides such architectural borrowings. The houses and Cypress trees she paints exist in Bel Air and other opulent Los Angeles suburbs, but for a moment we might believe she is painting Italian scenes. This ambiguity of place feeds as well into the aura of dislocation.

Preston was to fix on this theme as early as 1983, in her enamel on gatorboard composition, Bunker Hill, where the buildings of downtown Los Angeles rise like stark monoliths against a pale sky. There is also a road here, as in so many of her paintings of 1983 to 1985 – and we are seemingly invited to imagine ourselves entering the depicted scene along this thoroughfare.

Yet the center city locale, as rendered, is not at all inviting, even if it is visually seduction. These dark buildings do not appear suited for human habitation. Nor did Preston make her houses approachable, when she began to paint them again in the oil on canvas compositions of 1984. For instance, in elegantly structured pictures such as Road’s End and Dusk (1985), imposing steel grill gates block our way to lavish estates within.

Houses remain an important component of Preston’s recent paintings, as several compositions in this exhibition testify. Indeed, they have assumed increasingly greater symbolic resonance. Once again, In Forest Gate, the viewer is situated outside a gate. One is placed in this position of the voyeur or outsider; even a large round light visible through a window of the house seems aimed at the viewer. Yet the way this and other houses are lit make them feel too spooky for habitation. Both the interior and exterior of the House with Pines are a radiant orange, as if it were some extraterrestrial vessel which lowered itself n the crest of a hill. An orb, akin to a spotlight, shines directly at us in Circle of Light (1986). It is so large that it nearly conceals any view of the house nearby.

In general, then, artificial light has negative connotations in Preston’s oeuvre. It makes the houses in Ellwood House (1987), Green Shadows (1987) and Remember (1987), like those in House with Pines and Forest Gate, resemble hollow architectural shells. They don’t evoke the concept of home; indeed, they are emblems of our culture of mobility, in which the concept of home has become devalued.

With this group of her works, which we might designate her “house paintings,” Preston is also an heir to the very American sort of realism that Edward Hopper practiced. Her dark palette suggests links with the northern European romantics of the early 19th century such as Casper David Friedrich. But the rigorously formal structure of her paintings, coupled with her subtle critique of radical alienation, makes Hopper her more genuine ancestor.

To a degree, Near Paradise (1986) and several other pictures reveal a different aspect of Preston’s sensibility. For their light is brighter, the scenes more akin to traditional bucolic landscapes in the tradition of Claude Lorrain and his heirs. The vista in Near Paradise is reminiscent of many in 19th century American paintings, placing the viewer up high and providing him or her with the opportunity to gaze down on the richly varied scene. Yet the hedge shaped like a complex maze stands between us and the valley below. Any real paradise stands just outside our grasp; while in a related painting, Hedge (1987), we are situated inside the maze, it would seem.

Clearly, these tightly structured mazes are symbols of culture fashioned from nature. And they exist, in Preston’s paintings, to block our progress toward some bucolic paradise. In Near Paradise, the hedge disturbs the flow of the eye – and by extension, the body – on its progress into the paradisiacal valley below. In Maze (1987), the viewer is situated on one hill looking across at another. But blocking his or her mental passage from one to the other is yet another shaped hedge in the valley between them.

Thus the same theme assumes a different guise in these green landscapes. The scenes are not specifically Southern Californian; their terrain is more generic than that. But the mazes, like Preston’s gates, create a barrier between the viewer and the more distant part of the scene. In her suburban scenes, the house is the unapproachable destination; in the rural landscapes, the picturesque landscape itself is beyond our grasp.Even when there is no barrier, as in the structurally complex and beautifully conceived Green Passage, we stand at a far remove from this gorgeous place of smooth lawns and stately trees by the beach. We can gaze upon this verdant scene or look beyond it to the strip of blue ocean and expanse of pale sky which fill much of the top half of the painting. Yet we are never to get closer than this, for Preston has structured the picture so we stand far outside it, exiled from the paradise for which it is a visual metaphor. Ultimately, then, we do not gain passage into this “green passage.”

Nor does the artist, of course. But Preston’s art provides her with a bridge of sorts between the real world and this ideal world. Painting is a way of positioning one’s self above the maze, as it were, by giving the sensation of dislocation, of estrangement from nature, a coherent pictorial form. Landscape, like other genres, provides one with a way of structuring the world.

Preston has clearly extracted this truth as she has forged her vision of landscape. Her work strikes a fragile and evocative balance between the eye and the mind, the physical fact and its symbolic connotations. Like all strong landscape painters, Preston vividly conjures up the natural and manmade world. She is an adept translator of space, form and structure, as it exists in the world. But like all strong landscape painters, she also realizes that the depicted scene is a territory of ideas.