Astrid Preston

ESSAY BY RICHARD VINE

By Richard Vine

New York City, May, 1996

Deceptive modesty and sweetness inform the oil-on-canvas painting of Astrid Preston. Their scale – often as small as 4 by 6 inches – is almost self-effacing, their color harmonies are soothing, and their landscape-and-fruit subject matter seems unthreateningly bucolic. Yet, for all these blandishments, something troubling, and unexpectedly hunting, lurks behind Preston’s calm nature scenes. The artist, based in hyper-American Santa Monica, has taken on a great national theme. The venerable dialogue between wildness and civilization – between sheer abundance and productive order, between frontier liberty and Puritanical discipline – is here given a restrained but subtly inventive treatment. The organic artifice she portrays (and which her works materially embody) is itself, if not an ultimate solution, at least an exceptionally thoughtful comment on our culture’s ongoing dilemma.

Early in her exhibition career, Preston produced urban studies – sometimes in cut-out form, sometimes as straight paintings – centered on the natural and architectural icons of southern California: shorelines, palm trees, bungalows, glittering city skylines. Void of human figures, these works are pervaded by a sense of life gone socially, perhaps metaphysically, amiss. The viewer is invited to look past the pop-cultural surfaces that have enchanted artists like Thiebaud, Wesselmann, and Hockney to an emptiness beyond – a vacancy at the heart of the consumerist dream.

Because of the somberness of these early images, and because they were occasionally knit together from various photographic sources, critics tended to misapply the term “photorealism” to Preston’s work. Of late, a shift to dreamier and more sylvan themes has made the poetic – even allegorical – nature of her project increasingly evident. Meanwhile, she has developed several compositional strategies that mark her as a fully self-conscious, technically calculating artist.

Some recent paintings present modest, more-or-less straightforward landscapes, at times bathed in romantic mist effects, at times distanced from the viewer by labyrinthian hedges. Convincing as their “naturalness” may appear, these vistas are actually compounded of many climatically incompatible plant species, interspersed with flora of the artist’s own invention. She refrains from inserting human figures in order to keep the viewing experience as direct and first-order as possible. The trees themselves, she says, are in effect surrogate people. Indeed, Preston does not think of these scenes as conventional landscapes at all, but as esthetically determined “states of mind.” Her greatest formal influence here is traditional Chinese scroll paintings.

Other pictures emphasize their own contrivance by isolating a square of full-range color within an overall composition cast in a drab monotone (e.g., Rust Landscape), or by contrasting stylized but still relatively naturalistic fruit trees on the frontal plane with a background that modulates into pure geometric abstraction (e.g., Garden of Illusion). These may be windowlike views, but we are never allowed to forget that every window, every perspective, is a visual construct.

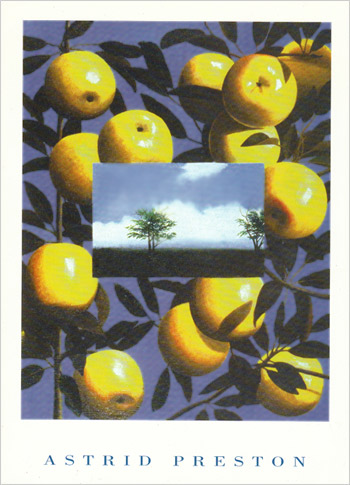

By far the most common, and most telling, device Preston now employs is that of the conceptually vertiginous picture-within-a-picture. In Lemon Tree, for example, four small canvases –two landscapes and two domestic architectural studies – hang among the elongated, super-yellow lemons on a single tree. More typically (in Apples and Landscape, Yellow Apples, and many other works), the voluptuous, high-keyed fruits – seen in tight close-up- surround and almost overwhelm the artwork in their midst.

Although she has lived since age 6 in the L.A. area, Preston seems to have imported one (perhaps unconscious) conviction from her birthplace in Stockholm. In contrast to the typical American preoccupation with natural grandeur (expressed in landscape images from the Hudson River school to Bierstadt to Ansel Adams), her works suggest the possibility of salvation through domestication and tidiness, at least when these pragmatic, often-disdained methods are intelligently considered – as they were by her architect parents. Her caution is especially understandable in view of the visual and ecological devastation that unrestrained “development” has wrought in California.

Eden, it should be recalled, was not a wilderness – and certainly not a megalopolis – but a garden. When Preston portrays nature-centered works of art (already an oxymoron) as a form of forbidden fruit, she taps into one of the most complex myths in the Western heritage. For her image-making implies that art, indisputable a form of knowledge, can be both our downfall and our deliverance. Artfulness may have originally alienated us from pristine nature, but in today’s technologically advanced world, nature itself can be preserved only through the most refined modes of artfulness.